A Handful of Sovereigns Read online

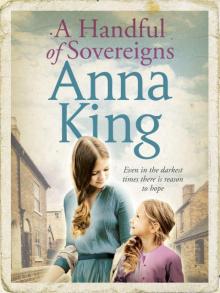

A Handful of Sovereigns

Table of Contents

Cover

A Handful of Sovereigns

Acknowledgements

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Copyright

A Handful of Sovereigns

Anna King

Acknowledgements

Dedicated to my sister Helen Midson (née Masterson), my brother-in-law Stuart and nephews Craig and Sean Midson

One

‘Will we have to go to the workhouse, Maggie?’

Fifteen-year-old Maggie Paige shot a startled look at her younger brother before answering quickly, ‘Of course not, Charlie, whatever gave you that idea?’

The young boy shrugged his thin shoulders, his white, pinched face giving him the appearance of a boy much older than his eight years. The sight of the desolation in her brother’s eyes caused Maggie’s heart to lurch painfully inside her breast. Putting out her hand she said softly, ‘Come here, love. Come and give me a cuddle.’

When the small arms wrapped themselves around her neck she swallowed hard, warning herself not to break down. The tears she had been holding in check all morning would have to wait a little longer, for now she had to be strong. Looking over his shoulder to where her sister stood by the door, she said gently, ‘Put the kettle on, Liz, and when the tea’s ready we can make a start on those sandwiches I made this morning.’

Lizzie Paige looked across the room at her sister, her eyes still red from crying and shook her head slowly.

‘I’m not hungry, Maggie.’

Fighting down a feeling of irritation Maggie strove to keep her voice steady.

‘I know you’re not, Liz, but we have to eat. We’ve had nothing since last night, and the last thing we need right now is for one of us to get ill.’

For a moment Maggie thought that Lizzie was going to start an argument, and prayed silently. ‘Not today, please God, not today.’ She felt her body slacken with relief as Lizzie walked slowly past her and into the scullery.

Shifting her weight slightly she leaned back against the horsehair sofa pulling Charlie with her. Stroking his hair gently she closed her eyes and thought back over the past week. Was it only a week? Could their carefree, happy lives have been so drastically changed in such a short space of time? She felt the tears begin to seep between her closed eyelids and swallowed noisily.

The first victim of the diphtheria epidemic that was running rife in the East End streets had been old Mr Blackstone in the basement flat. His sudden death had caused no more than slight ripples of alarm to run through the four-storey house in Bethnal Green, where they lived in the top two rooms. There was always some disease breaking out due to the blocked-up, overflowing sewers that were part and parcel of living in this area of London. Illness and disease were common occurrences that the people accepted with resigned endurance. Apart from taking the precaution of boiling their drinking water, her mother hadn’t taken any notice of the danger in their midst.

Then, a week after Mr Blackstone’s death, ten-year-old Billy Simms from the second floor came home from school complaining of feeling unwell, and within 24 hours he was dead. The other residents in the building had felt the first stirring of panic at the news of the young boy’s death, and their fears had soon become justified. Like a fire out of control, the disease had caught hold and swept through the large, overcrowded house, indiscriminate in its choice of victims.

Maggie hadn’t been surprised when the fever had claimed her dad, for he had always been sickly, spending more time at home than he did at the docks. Nor had it come as any surprise when her four younger brothers had succumbed to the sickness, for like their dad they had no constitution. But when her mum, that strong, single-minded woman that they had all looked to for guidance and strength had taken to her bed and quietly died, the shock had nearly been the end for the three of them. They had all loved their dad and brothers, but not with the fierce, almost worshipping feeling they’d had for their mum. Without her presence they were like a ship without its helm, floundering helplessly and without direction in a sea of pain and grief.

‘Tea’s ready,’ Lizzie muttered sullenly as she walked past Maggie and Charlie. Banging the teapot down on the green cotton tablecloth she pulled out a chair and slumped onto it dejectedly. Maggie looked at her sister’s dispirited face and felt the weight of responsibility bearing down heavily on her shoulders. Although Lizzie was two years older than her, Maggie knew that it would fall to her to see that the three of them stayed together.

Giving Charlie a gentle nudge she said kindly, ‘Come on, love, let’s get some grub down us, it’ll make us all feel better.’

Charlie hesitated for a moment. He wasn’t hungry, in fact he felt sick, but he must do as Maggie told him. From now on he must be very good, because if he was bad, then his sisters might send him to the workhouse. The very thought of that grim building was enough to send the bile rushing up into his throat. He felt the sweat break out on his forehead as he fought to keep from being sick, but it was no good. The days of grief and nights of fear he had endured this past week had accumulated until his nerve-racked system could take no more; when his stomach lurched he cast a beseeching look at Maggie before jumping down from the table and rushing into the scullery.

‘Well, so much for making us feel better,’ Lizzie said, her voice scathing as she watched the retreating figure of her brother.

Maggie looked up swiftly, her hackles rising at the tone of her sister’s voice. Her eyes raked over the small, plump figure dressed in the navy skirt and blouse with their mother’s black fringed shawl draped round the hunched shoulders and she felt her anger abating. Getting to her feet she asked mildly, ‘Pour me out a cup of tea, would you, Liz? I’d better see if Charlie’s all right, then we’ll have to talk about what we plan to do now that Mum and Dad have gone.’

‘What do you mean, have a talk? There’s nothing to talk about that I can see. We’ll just have to carry on like before but on less money, that’s all there is to it.’

Maggie stared at her elder sister in amazement. Was she being deliberately obtuse, or did she really think that their lives wouldn’t be affected by the death of their parents. But then hadn’t Liz always been the same? As far back as Maggie could remember, her sister had seemed to glide through life with her eyes closed to the problems of those around her. Only when she herself was directly affected, did she make an effort to stir herself, and it was this attitude that had been the cause of many a row between the two of them. With a resigned sigh she pushed back her chair and went in search of her brother.

Charlie heard her coming and tried valiantly to get to his feet, but the effort was too much and with a quiet groan he slumped back down onto the cold stone floor.

‘Oh, Charlie, oh you poor love,’ Maggie cried, her heart wrenching at the sight of the crumpled figure.

Bending down she put her arms under the thin legs and lifted him from the floor. Holding him tight against her breast she carried him into the front room and laid him down on the mattress in the far corner, then, kneeling by his side she took hold of his clammy hands and said urgently, ‘Charlie, you won’t end up in the workhouse, I promise. I’d never let that happen to you. I love you, you silly

ha’pence, and I’m going to look after you. Now try and get some sleep, there’s a good lad.’ Pushing back a tendril of damp hair from his forehead she took one last look at his ashen face before pulling the thin blanket over his trembling body.

‘What’s the matter with him?’ Lizzie asked as Maggie sat down at the table. Picking up a sandwich from the plate in front of her Maggie made a studious effort at eating in order to play for time before answering. Glancing sideways to where Lizzie sat, her fingers drumming impatiently on the table, Maggie was alarmed at the feeling of dislike that rose inside her at the sight of her sister. They had never been close–they didn’t even bear any resemblance to each other. Whereas Maggie was tall and slender with dark brown hair and eyes, Lizzie had always been on the plump side with fair, mousy hair and pale blue eyes, the image of her late father, while Maggie and Charlie had inherited their mother’s striking looks. This fact had been a bone of contention with Lizzie since the day she had started to take an interest in herself; and that interest had started very early in her life. The two girls had fought and argued as children, and growing into adulthood hadn’t softened their attitude towards each other. Maggie’s mind ran swiftly down the years, recalling all the petty grievances and squabbles, and felt a growing sense of dismay. There was no loving, understanding Mum now to intervene between them and restore order. Maggie had to admit to herself that she didn’t like her sister; she loved her, but she didn’t like her. She also knew that if it wasn’t for Charlie they would probably go their separate ways, but until he was old enough to look after himself they would have to bury their differences and try to create a stable environment for him to grow up in.

Pushing away the half-eaten sandwich she took a deep breath and said quietly, ‘What’s wrong with you, Lizzie? How can you sit there and ask what’s the matter with him? He’s only eight years old and he’s just seen his mum and dad and brothers buried. How do you expect him to act? The poor little sod thinks we’re going to put him in the workhouse, he’s half out of his mind with fear and if you weren’t so wrapped up in yourself you would have noticed before now.’

Maggie heard her voice rising and saw the flash of anger cross Lizzie’s face. Anxious to avoid an argument she reached out and grabbed the plump hand tightly, saying, ‘I’m sorry, Liz, I shouldn’t have said that. Please, don’t let’s fight, I know we haven’t always got on, but we have to forget the past and pull together now. If only for Charlie’s sake, let’s try and be friends, eh?’

Lizzie squirmed uncomfortably on the chair, her face a mixture of confused emotions while Maggie held her breath waiting for an answer. When she felt the hand within hers tighten she expelled a silent sigh of relief.

Lizzie remained silent for a few moments, then clearing her throat loudly she said awkwardly, ‘All right, I’m prepared to try to if you are. So what do you suggest we do now? How are we going to manage without Mum and Dad’s wages? I know Dad was more out of work than in it, but he did bring some money into the house, and Mum could sometimes earn as much as fifteen shillings from the washing and ironing she did for the big houses up Hackney and Aldgate way. I know I just said we could carry on like before, but I was just talking for the sake of it. We’re never going to be able to manage on our wages, are we?’

Maggie shook her head despondently. ‘Not while we stay on living where we are. The first thing we have to do is find somewhere smaller, we can’t afford to pay the rent here. First thing tomorrow I’ll start looking for another place. Mr Abrahams said I could have a few more days off while I sort things out; he’s been very good.’ As the image of her kindly employer appeared in her mind she found herself smiling fondly. Her mum had got her the job in the dusty, overcrowded book shop when she was thirteen, and for the past two years she had happily run the dilapidated, untidy shop whilst old Mr Abrahams had whiled his time away sitting outside the front of the shop in his wicker chair, puffing contentedly on his smelly pipe and chatting with anyone who happened to pass by.

Maggie knew she had been lucky to get such an easy, pleasant job, and had often felt guilty about Lizzie having to work in the matchbox factory in Bow. Conditions had improved slightly since the massive walk-out at Bryant and May in July, when 672 women had downed tools in support of a young girl unjustly sacked. This unbelievable action had led to an all-out strike, during which time Lizzie had been in her element. Every day she had gone down to the factory and taken her place in the picket line holding aloft her makeshift banner, retailing with relish the horrific conditions to the throng of curious bystanders who gathered to witness the historic event. For the first time in her life she had felt important, and although her wages had been sorely missed until strike pay had been organised, it had been almost worth the extra hardship to see her happy for a change.

‘What do you mean, somewhere smaller?’ Lizzie’s voice shrilled loudly, cutting into Maggie’s reverie. ‘How much smaller were you thinking of? We’ve only got two rooms and a scullery as it is, if you think I’m moving into something even smaller you’ve got another think coming. Now you listen to me, Maggie, I…’

‘No, you listen,’ Maggie hissed back. ‘You earn nine shillings a week, I only get five and sixpence. The rent here alone is twelve bob, and that’s without food, coal and money for clothes and shoes; you work it out. And as for this place being too small, it was big enough for the nine of us for years, wasn’t it?’

The two girls glared at each other, their short-lived friendship gone, swept away on the tide of anger engulfing them both. An uneasy silence settled on the room, and then, her body heaving with rage and frustration, Lizzie leant towards Maggie and said savagely, ‘Oh, yes, it was big enough for nine of us, with Mum, Dad, Harry, Johnny, Jimmy and Ken packed into one bedroom and you, me and Charlie huddled together on a mattress hardly big enough for two people in the same room we use as a kitchen and sitting room. Huh.’ She was on her feet now, her hands resting on the table, her face inches away from Maggie’s.

‘And as for the money we bring home, you could help there by giving up the bookshop and getting a real job. It’s not fair that I should have to slog my guts out in that stinking factory while you ponce around dusting old books pretending you’re someone special. But then Mum thought you were, didn’t she? She didn’t drag you down to the factory when you left school like she did me, oh, no, not her precious Maggie, she wanted something better for you. Never mind that I’ve risked having the jaws eaten out of my head by phosphorus for the past four years working in that hell hole. As long as I brought my wages home that’s all that mattered to Mum.’

Maggie sat rooted to her chair, her eyes wide with pity and sudden understanding of her sister’s animosity towards her over the years. If the positions had been reversed, wouldn’t she have felt the same?

‘Liz, I’m sorry,’ she murmured softly, ‘I had no idea, I just never thought about it–you’ve never said anything before.’

‘What good would it have done to complain?’ Lizzie replied bitterly. ‘The factory’s bad enough, but there are worse places so I kept quiet. But there’s hardly been a day gone by when I haven’t thought of you working in that bookshop while I’ve stood at my bench pasting strips of magenta paper and thin pieces of wood together. I’ve become fast over the years, that’s why I can earn up to nine bob a week. But when I first started my fingers used to be rubbed raw trying to fill my quota, some days, when the foreman was breathing down my neck and I was scared I’d lose my job, I’d work even faster until my fingers bled. I… oh, what the hell.’ Her voice broke, and when Maggie saw the tears spring into her sister’s eyes she pushed back her chair, and going to Lizzie’s side she placed an arm around the heaving shoulders. Gently turning the sobbing girl around, Maggie led her to the sofa and together they slumped down onto the worn cushions. As they sat side by side, their arms closely entwined, Maggie felt a sense of peace and well-being steal over her. But the moment was short lived, as Lizzie, recovered now from her crying spasm and feeling awkward

at being in such close proximity with her young sister, quickly disentangled herself from Maggie’s grasp.

‘Well now,’ she said gruffly, ‘I’d better get back to work. If I hurry, I can still get an afternoon’s work in. Like you said, we’re going to need all the money we can get now.’

‘But, Liz, we haven’t had a proper talk yet,’ Maggie’s voice rose in alarm. ‘There’s such a lot to be sorted out–can’t you take the rest of the day off?’

Lizzie was already pulling on her heavy black shawl, her face impassive as she made for the door. ‘We need the money,’ she repeated dully. Maggie stood watching her for a moment, then with a quick bound she was across the room, her hand clutching at the plump arm.

‘I’m going to go and see Mr Abrahams tomorrow and tell him I won’t be able to work for him any more.’ The words tumbled out breathlessly while her mind reeled in shock at the enormity of what she had said.

Shaking her head impatiently she carried on, ‘You’re right, it isn’t fair to expect you to carry on in a job you hate when I’m so happy in mine. I thought maybe I could take over Mum’s job. Her customers will still want their washing and ironing done, and that way I can stay at home and keep an eye on Charlie. He needs one of us to be around right now. You know how nervous he is, and he’d hate coming home from school to an empty house. And… and if I can persuade Mum’s customers to let me do their laundry for them, then maybe we can stay here after all. What do you think, Liz?’ Her hand tightened on Lizzie’s arm, her voice pleading for some kind word, however small–but she was disappointed.

Shrugging her arm free, Lizzie opened the door, then turning her head slightly she said tersely, ‘If you’re waiting for a pat on the back, you’re out of luck. It’s about time you found out what hard work’s really like, you’ve had it easy for far too long. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m late for work.’

When the door was slammed in her face Maggie stood for a long moment staring in hurt silence at the stained wooden panels, and then her mood changed swiftly to anger. Her fists clenched into tight balls, she stormed across the cracked, lino-covered floor and into the bedroom that had belonged to her parents and younger brothers. Ignoring the brass bedstead and the bare, stained mattress she sat instead on the long wooden ottoman at the foot of the bed. Placing her fists between her knees she rocked her body back and forth all the while muttering, ‘The cow, the nasty, spiteful cow. How could she know how hard I’ve worked?’ What about all the times she had had to carry heavy boxes of books from the big houses down to the shop? And how about when she’d had to haggle a price for the books, some of which were fit only for the rubbish tip, while the so-called better-classed ladies and gentlemen had treated her as if they were bestowing a great favour in allowing her to take their prized possessions away.

Palace of Tears

Palace of Tears Ruby Chadwick

Ruby Chadwick A Handful of Sovereigns

A Handful of Sovereigns Whenever You Call

Whenever You Call The Ragamuffins

The Ragamuffins Fur Coat, No Knickers

Fur Coat, No Knickers Luck Be a Lady

Luck Be a Lady Maybe This Time

Maybe This Time